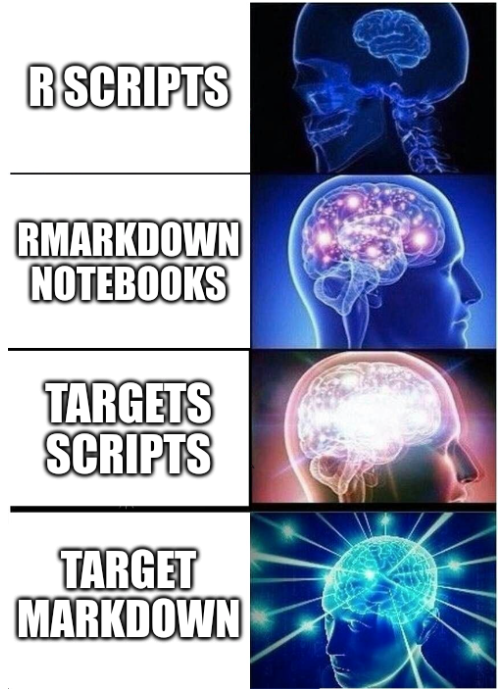

I wanted to dedicate a (no so) quick post to a package that has really changed my way of programming in R: the targets package. This is definitely a tool I wish I had known during my PhD! In order to introduce why in my opinion targets is such a brilliant package, I need to talk about my journey as an R user.

Beginner

I started learning about and using R at university. At that time, I started saving my code as R scripts. Basic, but gets the job done.

Intermediate

The real fun began when I learned about Rmarkdown. At the time I was actually using Sweave, but that’s a very similar experience. Not only could I write R code, but I could record any comments about the analysis and my interpretation of the results alongside the code in a single document. So efficient! Rmarkdown quickly became by default choice when writing any R code. During my PhD, I used several Rmarkdown notebooks to record the different steps of the (complex) analysis that I was working on. I started numbering my notebooks (1_preprocessing.Rmd, 2_normalisation.Rmd, etc), and also saving them into different folders according to the analysis step (dataset_X_analysis, dataset_x_some_followup analysis…).

This approach became a bit tedious as my notebooks became longer. For example, when I wanted to work on an analysis started previously, I had to run the previous code chunks. But often I didn’t need all of them because my work was very much exploratory, so some sections were irrelevant to the current task. And going fishing in the report which chunks needed to be re-run was not always easy, and sometimes downright frustrating.

Some chunks contained commands that took a long time to run. As I had to re-execute the entire rmarkdown every time I wanted to update the report, this was problematic. So I implemented my own cache system (at the time for some reason I wasn’t aware of the cache option of R code chunks): I would run the long calculation, save it as a .Rdata file in a folder called processed_data/ and then turn of the chunk evaluation with eval = FALSE. Then underneath the code chunk, I would add another code chunk to read in the .Rdata file.

Sometimes the computation was too demanding to run on my own laptop, and instead I had to run the command on a virtual machine accessible only through a terminal (no Rstudio to play with the report interactively). In order to do that, I had to save all intermediary results that the command depended on, and then copy the code that needed to be executed into an R script. I transferred all of that on the virtual machine. Then I had to save the result into my processed_data/ folder, and remember to copy any changes I made to the code back into the notebook.

Despite these hacks, this cache system worked well for a while. Until I had to switch computer. Now, I have been using Github since uni, so all my code was backed up. The cache, of course, wasn’t. But it’s fine, because everything is reproducible, right? Well. In order to rerun the entire analysis, I had to open each Rmarkdown notebook one by one. I had to find the chunks whose evaluation was turned off, turn them back on, and turn off the evaluation of the chunks that read from the cache. Then I had to knit the notebook. This could be long, and sometimes would crash in the middle, because of a missing package for example. Then I had to reverse the changes I’d made so that next time I knitted the notebook, the long commands wouldn’t be executed. It now seems very convoluted, and learning about the cache option would have saved me a lot of time. But it’s not the only problem I had with notebooks. There were also the times when I would want to change one little thing in the report, but this meant re-evaluating the entire notebook. Or realising that the data had changed but I had forgotten to re-run some of the commands with cached results, so my analysis was actually out of date. Not very fun, when you’re on a deadline to submit your thesis.

Enters, the targets package.

Advanced

A colleague told me about the targets package. He suggested that I use it for a project that I was starting, which was about developing an analysis pipeline. So I looked into it. And I have to say, the authors of the packages have really made it easy to use targets, thanks to their amazing manual. And I quickly fell in love. The idea is that you organise your (very long) analysis into a script consisting of many little steps, and the package detects the dependencies between the steps. When you execute your script, the output of each step is saved, so that you can then load it in memory and work with it. No more having to execute an entire notebook just to get this one data-frame to tweak this one plot. Even better, it records the state of the analysis pipeline, so that it knows which steps are up to date, and so will skip them when you re-execute the pipeline, and which ones should be run again because you’ve modified some other step they depend on (I know my explanation is not ideal, so you should really go and read the manual!). You can also track files, so that it knows that your analysis is outdated if the data file changes. And you can visualise your pipeline as a graph!

One of the big advantage of working with targets is that you can de-couple the analysis run step from the report rendering step. That is, you can create all of the plots and tables etc in your target pipeline, and load them in the report. This way, if you want to tweak something in the report, it is very fast to render, because there’s no computation involved in the report, only reading in the output from your pipeline. And the best part is, you can include rendering your report as a part of your pipeline, so that it is rendered every time an output it depends on has changed.

But…

Expert

One thing that bothered me about targets scripts was around collaboration. At that time I was transitioning to a job where I was expecting to collaborate a lot more and share my code with my colleagues. And the thing about targets scripts is that, well… it is an R script. So the ability to describe your code and thought process is pretty limited. You can always add comments, but after working with Rmarkdown for a long time, this looked like a step backward. Then I arrived to the Literate Programming chapter of the targets manual1, about Target Markdown. And I found this so elegant. You can write a Rmkardown file, where you define your targets in targets chunks. Then when you knit the notebook, it generates the target script for you. You can even add the command to run the entire pipeline at the end. This way you can create a report that contains the code you used for the analysis alongside any explanations, using all of the amazing features that Rmarkdown has to offer. But your analysis is executed as a targets pipeline, which gives you all the caching and monitoring features of the targets package. When I am ready to share my code with others, I can provide them with the Rmarkdown file as well as the knitted report, so they can reproduce the analysis, but also read through the narrative of the analysis in a reader-friendly format (I personally like to knit my documents as both md documents that are readable from GitHub, and html for sharing outside of GitHub).

Conclusion

Today, a few years after drafting this post, I am now back to using targets as a script, rather than through Target Markdown. I found that it was quite a complicated set-up for a small return, since I didn’t end up sharing my code with others as often as I initially thought. But I still think it’s valuable to know, and I am very happy that this option still exists should I need it one day!

Footnotes

The relevant content has now been moved to Appendix C of the targets manual.↩︎